Blog #150 – Final Exam – En-gendering the Causes of the Spanish-American War.

Throughout the year, we use different lens with which to analyze certain events – we can analyze events or people’s actions through an economic lens or a political lens or a social / cultural lens. During our Reconstruction unit, we used a racial lens to look at how Reconstruction policies affected free Blacks. Now, we turn to American imperialism and instead of analyzing American foreign policy, or our relationship with other nations, through a diplomatic lens or a commercial lens, I am asking you to use the lens of gender to explore the Spanish American War. This angle was originally presented by historian Kristin Hoganson in 1998. To help you answer the questions raised by this blog, you’ll need to have read the article, “En-Gendering the Spanish American War”.

The question that this gender lens attempts to ask is, is there another way of looking at the causes of the Spanish-American War?

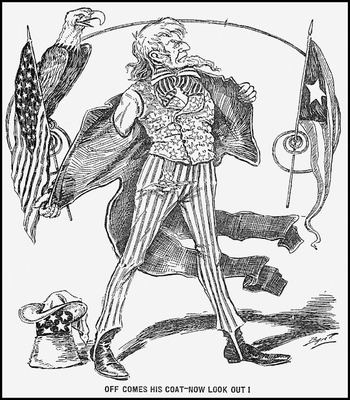

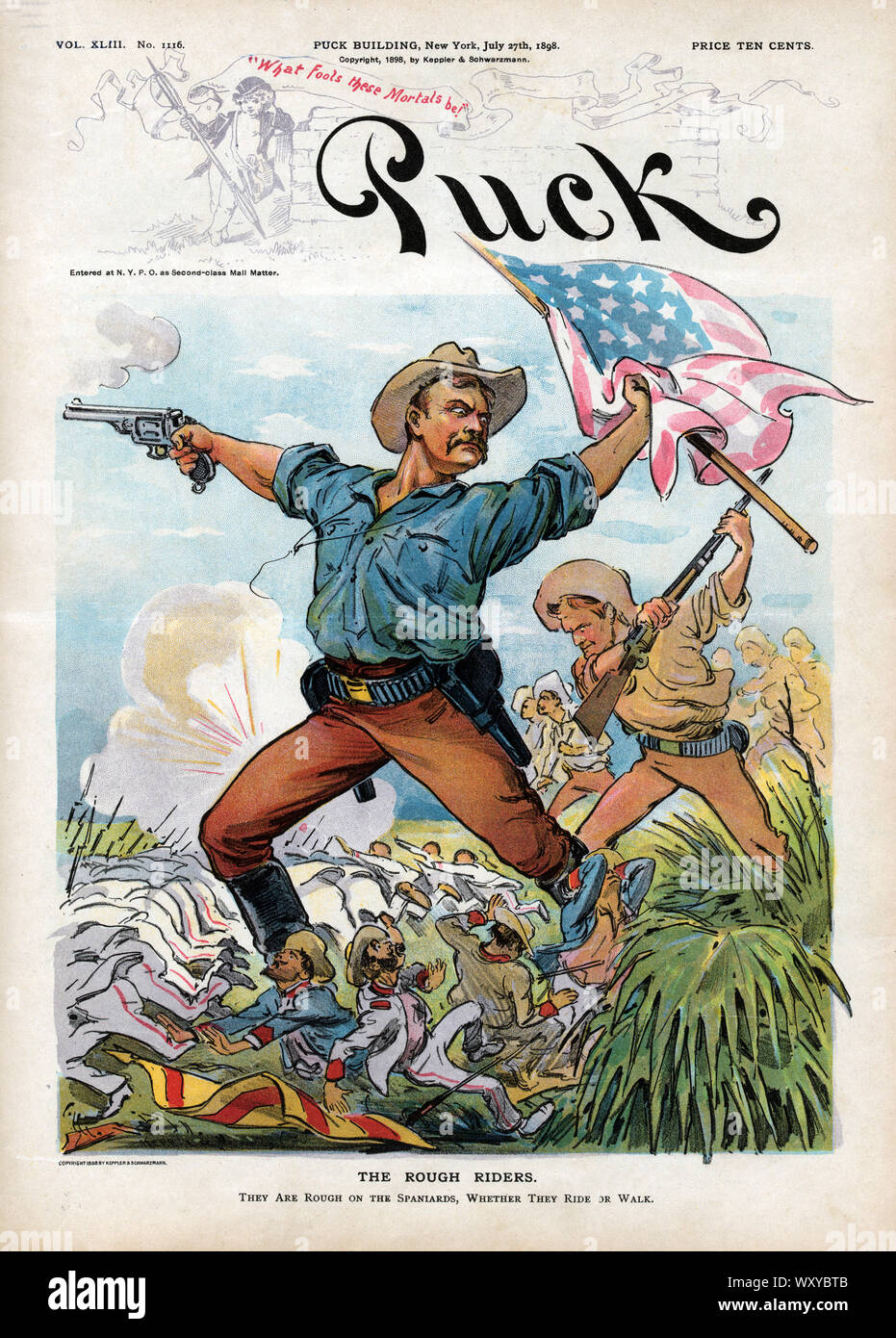

First, some context for Teddy Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill in Cuba during the war. He was part of a generation of Americans who were raised on glorious tales of Civil War gallantry told by the veterans of the war. TR’s generation of men aspired to have their own fight where they could test their courage and honor, and the Spanish American War provided such a chance hopefully without the grizzly slaughter of four years of a civil war. Also, TR’s father had not fought in the Civil War being too busy making money (and also paid a substitute to take his place). Furthermore, TR grew up as a very sickly, asthmatic child who was very fragile until he reinvented himself in his 20s out on the Great Plains in North Dakota raising cattle in the summers. It’s likely he never thought that when he was a boy listening to stories of valor at Gettysburg would he get a chance to do the same thing and face an enemy with bullets flying at him. Lastly, when the war started, TR resigned his post in the McKinley administration as Assistant Secretary of the Navy to form his own militia unit for the war which was dubbed by the press, “the Rough Riders” but he called this militia unit the Children of the Dragon’s Blood. TR would also later go on to defend what he would call “the strenuous life” which included playing manly sports, continual exertion, challenging nature through hunting and exploration, cleaning up corruption, busting trusts, and waving around the ultimate symbol of his manhood, his “big stick” in the international arena.

So why did America come to the defense of the Cubans in 1898? The article lists the following possible reasons:

- commercial rewards of empire

- an extension of a global Manifest Destiny

- a quest for naval bases

- humanitarian concerns for the Cubans

- a chance to enact some Christian “uplift” for the people who are “freed”

- glory

- revenge for the destruction of the U.S.S. Maine

- motivated / inspired / enraged by yellow journalism in the newspapers of Hearst and Pulitzer

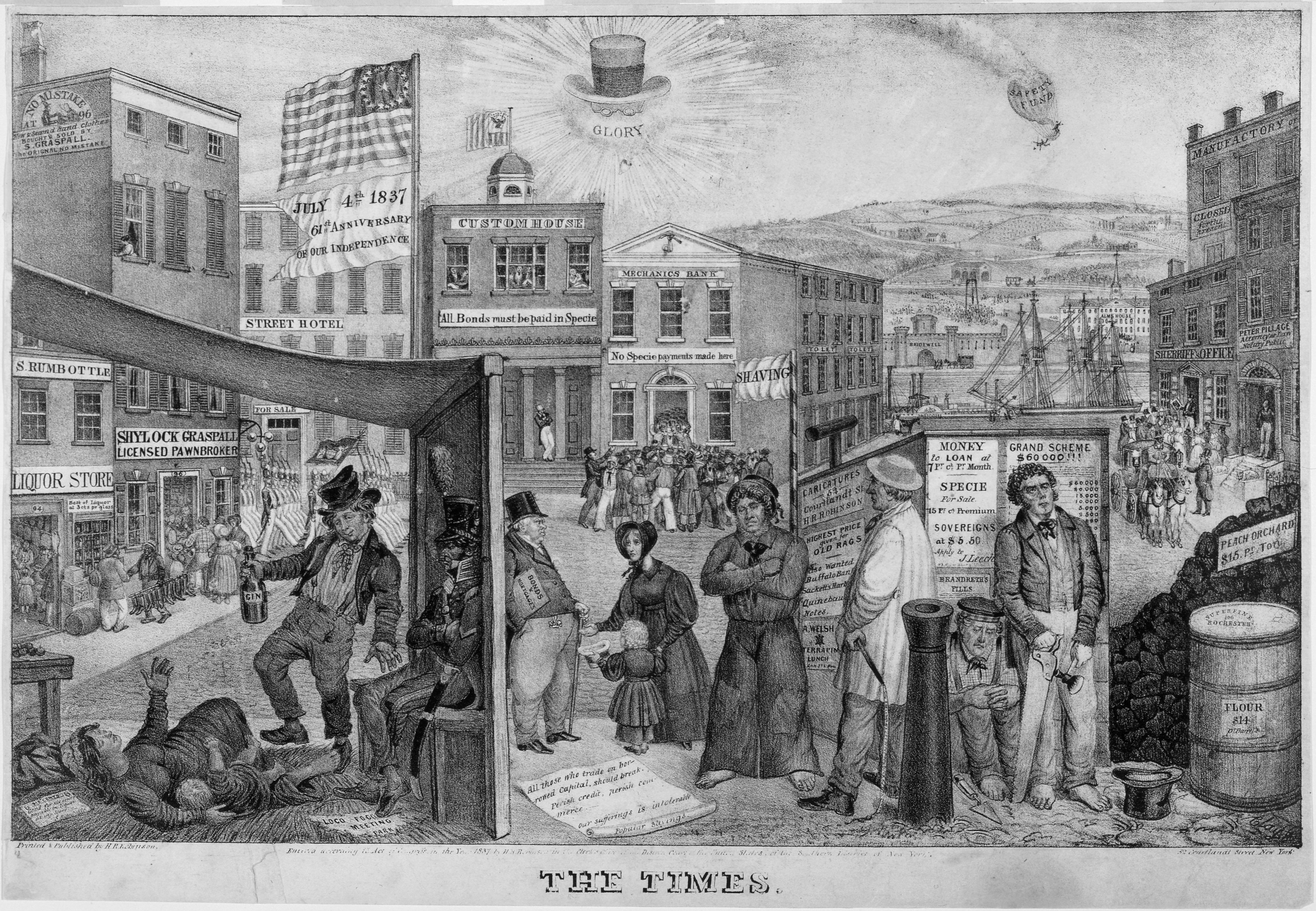

But the article proposed another cause – a crisis of upper and middle class white manhood. There seemed to be threats to traditional notions of manhood all around – the creature comforts of an industrial America were making men “soft” and “sluggish”; making money by bending or breaking ethical norms seemed to corrode the traditional manly sense of honor and integrity; some men lost their jobs, their self-respect, and their independence and vitality because of the Depression of 1893; but possibly most shocking was the rise of the “New Woman” who wanted the right to vote and participate in politics (traditionally the man’s responsibility). In this new era, women’s virtue was considered by many to be superior to men’s because of all the economic, social, and political problems that men’s “virtue” had caused from 1865-1898 that the Progressive Era would try to solve was trying to solve. I mean, let’s remember that many middle and upper class white women were leading the reformist charge during that era.

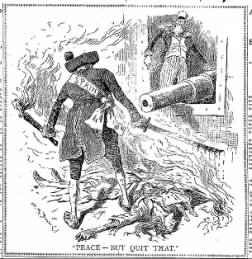

Let’s take a look at another cartoon from this time period. Here’s a cartoon from Puck (which is normally anti-imperialist compared to its counterpart, Judge).

Done by artist Louis Dalrymple, published in May, 1898. The caption reads, “The duty of the hour – to save her not only from Spain but from a worse fate.” After reading this article, I’d like you to interpret this cartoon through the gendered lens mentioned in the article.

Your job – answer the following questions:

- Do you agree with this gendered interpretation of the causes of the Spanish American War? Why or why not?

- What is a strength of using this lens? What is a weakness? Explain.

- Interpret the cartoon above of the Cuban woman in a frying pan (or the one below of the Rough Riders) using the gender lens. Describe in detail how you can use gender to interpret different aspects of the cartoon.

A minimum of 400 words total for all three answers. Due by 11:59 pm, Sunday night, March 12.

An article on how the Span-Am War led to American empire – https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/1785

An analysis of the American / British alliance that grew out of the Span-Am War as shown in cartoons – https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/civilization_and_barbarism/cb_essay02.html

In an August 2017 statement on the monuments controversy, the

In an August 2017 statement on the monuments controversy, the  by you.” A different example from the article is what the University of Virginia has done in the past decade in trying to honor its slave past. At least 140 slaves helped build the university, and this fall, Virginia opened up a dorm named after two of the slaves who had worked on the campus before the Civil War.

by you.” A different example from the article is what the University of Virginia has done in the past decade in trying to honor its slave past. At least 140 slaves helped build the university, and this fall, Virginia opened up a dorm named after two of the slaves who had worked on the campus before the Civil War.