Blog #94 – “Prisoner of war camps” = Indian reservations?

As we study Andrew Jackson’s legacy with regards to the Native Americans, one thing to keep in mind is the long-term legacy that white Americans have to own with regards to Native Americans. Jackson and Van Buren expelled the Indians, the Five “Civilized Tribes” of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Seminole, Choctaw, and Creek tribes – under the Indian Removal Act. They were relocated to lands west of the Mississippi River where they would be allowed to roam free, the thinking went. In the video we saw this week, Andrew Jackson: The Good, Evil, and the Presidency, Natives suffered tremendously. But that was only one act in this long drama between white Americans (and previously before them, white Europeans) and Native Americans.

The Indian Removal Act was passed by Congress in 1830, in order to remove the five tribes from areas of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Historian and noted Jackson scholar Robert Remini said that the Indians were removed from the eastern United States because they presented a direct threat to the country, having been used as sabotuers by foreign invaders in the past three wars that America had fought (French and Indian War, the Revolution, and the War of 1812). Remini saw this act as improving the homeland security of the nation. Other historians see the act within the context of the grab for new farm land in the cotton-growing frenzy that gripped the nation – the Indians were moved because the land they lived on was coveted by white farmers so that they could add to the cotton kingdom. This act was unconstitutional because the Indians were seen as sovereign nations living within the U.S. in Article IV, Section 3, and even the Supreme Court affirmed that the Cherokee couldn’t be moved in Worcester v. Georgia. Historian H.W. Brands states that President Jackson felt that this removal policy was “humane” and saved the Indians from annihiation from the crushing forces of white encroachment.

From there, however, Manifest Destiny charged ahead, damn the torpedoes, so to speak, and the Indians were in the way again. Whether it be farm land, gold and silver mines, railroads, or the destruction of the buffalo, Native Americans became an easy target for white Americans moving westward. The tribes were pushed aside and put onto reservations, or as the speaker in the TED talk below, Aaron Huey, calls them, “prisoner of war camps”. Some Indians like Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Crazy Horse, just to name a few, fought back and succeeded at slowing down the demographic tide.

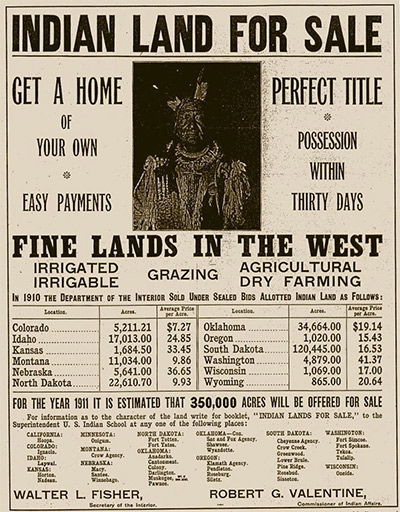

For most American history books, we see that they talk about the Indians almost always when they are being pushed off of their land by Europeans (King Philip’s War, Powhatan War, Seminole War, Indian Removal Act) or when they fight back (Battle of Little Bighorn, Red Cloud’s War) or after being indiscriminately massacred (Sand Creek and Wounded Knee Massacres). Few cover the decimation of disaeases that faced the Native Americans when the Europeans first arrived. Even fewer touch on 20th Century issues and laws regarding education, reservation (and sale of Indian land), tribal recognition, citizenship, Termination policy in the 1950s or other Indian policies like the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Our textbooks might talk about AIM or the standoff at Wounded Knee in 1973, but just as an inclusion of many minority groups in the chapter on the late 1960s / early 1970s. There might even be something about the seizure of Alcatraz Island by Native Americans. But rarely anything is heard after that.

In the following disturbing and moving video, photographer Aaron Huey lists the many things done (in the name of America) to the Lakota Sioux tribe. He juxtaposes the litany of broken treaties and promises and horrific things with his own photos of the Lakota tribe at Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Aaron Huey’s wish is that the American government honor the treaties and give back the Black Hills. To atone for America’s sins, to use such a phrase, can anything truly be done? Where, if anywhere, should Americans start to make up for what has been done to the Native Americans? Is it right that we should speak in such manner as atoning for sins or asking for forgiveness? Or do you feel that you have nothing to ask forgiveness for since these things had been done before you were born? What responsibility do we have to Native Americans?

One major thing to consider is that though we may not have been personally responsible for oppressing the Native Americans, we benefit from the results of past policies of our government towards Native Americans (and even from past colonial practices).

Should we replace Columbus Day with Indigineous Peoples’ Day?

Should we push Congress to rescind the Medals of Honor distributed to the 7th Cavalry handed out after the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890?

Should reservations be abolished? Or should those that exist still remain yet receive generous help?

Should the Washington football team, the Cleveland Indians, or Atlanta Braves be forced to take new mascot names?

What can we learn from Canada and the way they have treated and honored their Native Americans?

Should we continue to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline (since President Trump has rescinded President Obama’s cancellation of it)?

Should Native Americans be given back their religious ceremonial artifacts, tens of thousands of which sit in museums, some on display, others locked in vaults? (for an upclose perspective, see the recent PBS film, What Was Ours here).

In finishing up the research for this blog (including reading chapters of the book, “All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz) I found that Congress passed, as part of an appropriations bill, a resolution called the Native American Apology Resolution in 2009. Introduced by Republican senator from Kansas, Sam Brownback, he said the reason he did this was “to officially apologize for the past ill-conceived policies by the US Government toward the Native Peoples of this land and re-affirm our commitment toward healing our nation’s wounds and working toward establishing better relationships rooted in reconciliation.”

Furthermore:

The Apology Resolution states that the United States, “apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States.”

The Apology Resolution also “urges the President to acknowledge the wrongs of the United States against Indian tribes in the history of the United States in order to bring healing to this land.”

The Apology Resolution comes with a disclaimer that nothing in the Resolution authorizes or supports any legal claims against the United States and that the Resolution does not settle any claims against the United States.

The Apology Resolution does not include the lengthy Preamble that was part of S.J Res. 14 introduced earlier this year by Senator Brownback. The Preamble recites the history of U.S. – tribal relations including the assistance provided to the settlers by Native Americans, the killing of Indian women and children, the Trail of Tears, the Long Walk, the Sand Creek Massacre, and Wounded Knee, the theft of tribal lands and resources, the breaking of treaties, and the removal of Indian children to boarding schools.

- Tell us your reactions to the Ted Talk;

- Discuss your thoughts / concerns about how to acknowledge the debt America owes Native Americans and why.

400 words minimum for both answers. Due Wednesday, February 1.

Extended quotes come from the blog: https://nativevotewa.wordpress.com/2009/12/31/president-obama-signs-native-american-apology-resolution/