Blog #119 – Indian mascots – insult, honor, or something else?

In the February 2012 article, “Insult or Honor?”, the author examines reasons surrounding the controversy of using Indian names and tribes as mascots for athletic teams. But first, a little history:

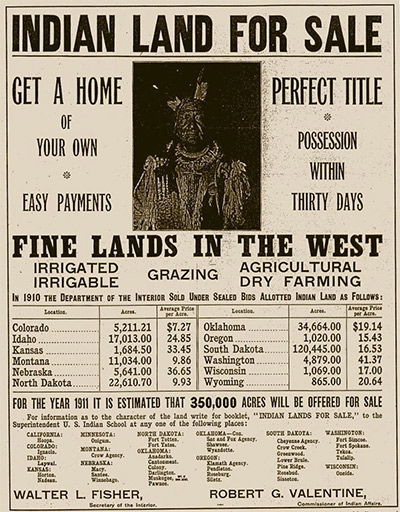

The Boston Red Stockings changed their team name to the Boston Braves in 1912 (which would then move to Atlanta to play baseball there), and the Cleveland baseball team changed their mascot name to the Indians in 1914, purportedly because one of their players was a Native American. College teams had had Indian mascots for decades, but Stanford University became one of the first universities to change their name voluntarily in 1972 from the Indians to the Cardinal. In the 1990s, the NCAA ordered all teams with Indian mascots to change their nicknames and logos unless the university got permission from the tribe associated with that school. Only a few schools were able to keep their mascots: Florida State, University of Illinois, University of Utah were a few. In 2005, the NCAA put 19 colleges on notice that their names were “hostile or abusive” to Native Americans, and apparently all of the schools have changed except for Alcorn State University in Mississippi. The high school mentioned in the article, Mukwonago, was ordered by the Wisconsin legislature to change its name (Warriors) to something else. The case ended up in court, and the state courts allowed the school to keep its mascot and nickname in 2015, but they haven’t decided to change it back to the Warriors.

Arguments for keeping the Indian mascots include tradition and honor to those tribes involved. Another argument for keeping the mascots revolve around financial means. Those schools affected would need to buy all new sports uniforms, change gym floors and paint over murals at stadiums and gyms. The article estimated that there are 6,500 schools of all levels that use an Indian mascot. As for pro teams like the Washington R____, Atlanta Braves, Kansas City Chiefs, Chicago Blackhawks, and Cleveland Indians, they have argued that it would be too expensive to change their gear. The Cleveland baseball team recently dropped its Chief Wahoo mascot and now just goes with a bright red C.

The primary arguments against using Indian mascots and names primarily rest with the thought that these are insults to Native peoples and engage in harmful and hurtful stereotypes. Chief Wahoo can be found at the Ferris State Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia because it represents the “Red Sambo” character in Jim Crow iconography. Stereotypes like this have been used to justify racist behavior and discriminatory laws. An additional argument can be that when white fans of these teams dress as Indians, they are appropriating the Indian culture and making a mockery of it (kinda like when people dress like hippies for 60s day during Spirit Week). The most egregious / extreme use of the Indian nickname that causes hurt is the NFL franchise found in Washington D.C. In 2013, the owner of the team, Daniel Snyder, has said, “We’ll never change the name. … It’s that simple. NEVER—you can use caps.” In 2014, 50 U.S. Senators (48 Democrats and 2 independents) sent a letter to NFL Commissioner, Roger Goddell, asking that the NFL not support racism and bigotry. Supposedly, the name was chosen in 1933 to honor all Native Americans. However, if this were done with any other group of people, including whites (The Detroit Blacks, for instance, or the Pittsburgh Whites – all made up names), many people might have an issue with that. However, in a 2017 case that went before the U.S. Supreme Court, a band known as the Slants (made up of Asian Americans) won a case against the U.S. trademark office because by the government refusing a trademark for the Slants, that would be a violation of their free speech. Snyder sees this victory for free speech as a victory for his team since the Trademark Office had recently voted to cancel his team’s trademark in 2014.

Here’s a commercial put together by the National Congress of American Indians about the mascot issue:

So what’s your position on the use of Native American nicknames as mascots for schools and college and pro sports teams? Do these names show what the predominantly white attendees say they do – courage, spirit, honor, and respect? Should a school get the local tribe’s permission in order to use its tribal name (like the University of North Dakota or Eastern Michigan and Central Michigan)? Or is it time to retire these relics of a racist past to the trash bin of history?

Your answer is due Tuesday (4/23) by class. 300 words total.

A video from Fox News debating the issue below: